Imagine a classroom where students are captivated by the rhythm of a story, their imaginations ignited with every word. Reading aloud does more than entertain; it builds critical language skills and fosters a lifelong love of learning. Using classroom time for read-alouds is not just beneficial but essential, as it provides students with unique opportunities to develop literacy skills that are foundational for their academic success. Let’s explore how this simple act creates a profound impact on literacy development.

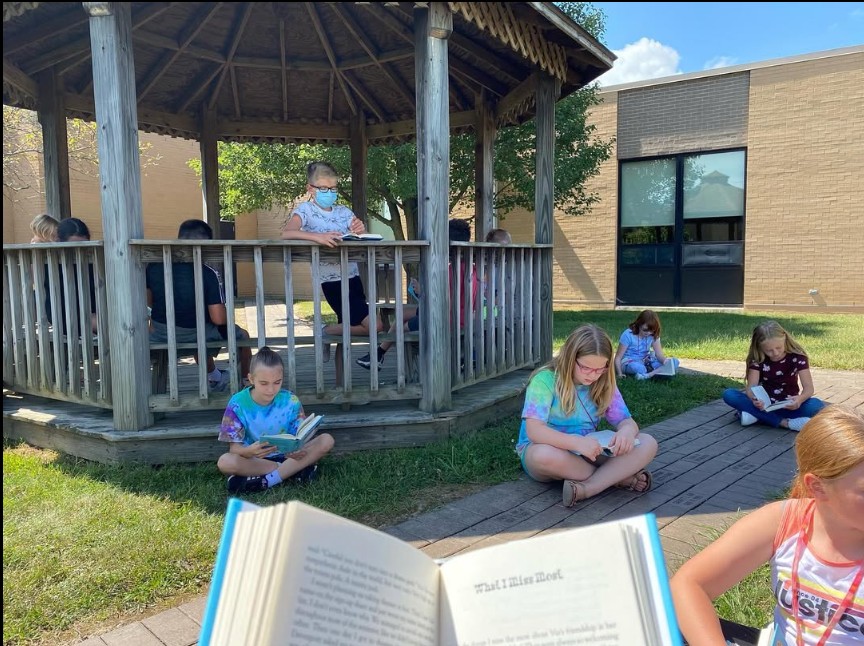

Read to them.

Every age. Everywhere.

Every Day.

Unlocking the Hidden Power of Written Language

Spoken language is often simple, informal, and repetitive, while written language tends to be more complex, structured, and varied. When children listen to books being read aloud, they are exposed to sentence structures, vocabulary, and phrasing that go far beyond conversational speech. Written texts often feature longer, more intricate sentences and a broader range of linguistic elements, while everyday conversation tends to rely on simpler, repetitive structures. For example, a casual conversation might include phrases like, “Let’s go over there,” whereas a written text might say, “They ambled leisurely toward the shaded grove, their footsteps muffled by the soft forest floor.” This exposure equips children with the skills to navigate complex language in their own reading and writing. This exposure builds a foundation for literacy by familiarizing young brains with the patterns and nuances of written communication (Montag, Jones, & Smith, 2015).

Key Insight: Children who hear written language develop an understanding of how sentences are constructed and how ideas are organized, which is crucial for reading comprehension and writing skills.

Classroom Tip: Select books with rich language, varied sentence structures, and complex ideas to broaden students’ linguistic exposure.

Supercharging Vocabulary Through Storytime

Reading aloud introduces children to rare and sophisticated words that rarely appear in everyday conversation. For instance, words like “verdant,” “benevolent,” or “serendipity” often appear in children’s literature but are unlikely to be used in daily speech. These words enrich a child’s vocabulary, giving them tools to express more nuanced ideas and thoughts. Research indicates that children’s books contain three times more unique words than speech, giving young listeners a substantial advantage in vocabulary acquisition (Hayes & Ahrens, 1988). A strong vocabulary is one of the best predictors of reading success.

Key Insight: Listening to books helps children develop a “word bank” that supports decoding, comprehension, and expressive language skills.

Classroom Tip: Pause during read-alouds to explain unfamiliar words and encourage students to use these new terms in their own speech and writing.

Brain Boost: How Stories Strengthen Neural Pathways

Hearing written language activates brain areas associated with storytelling, sequencing, and comprehension. This brain activation supports long-term literacy by strengthening the pathways needed for decoding, understanding, and synthesizing text—skills that are critical for academic success across all subjects. Neuroscience research has shown that listening to stories read aloud strengthens connections between the auditory processing and language centers of the brain (Hutton et al., 2015). These connections are critical for developing the ability to decode and understand text independently.

Key Insight: Children who are read to regularly show more robust brain activity in regions linked to language and literacy.

Classroom Tip: Make read-alouds a consistent part of your day, even for older students, to support ongoing brain development.

Fluency in Action: Modeling the Music of Language

Fluency involves reading with accuracy, speed, and expression—skills that are reinforced when children listen to proficient readers. By hearing how written language sounds, students learn to mimic proper pacing, intonation, and phrasing. This auditory exposure creates a mental model of fluent reading that they can replicate in their own practice (Rasinski, 2014).

Key Insight: Listening to fluent reading builds auditory fluency skills, which transfer to independent reading performance.

Classroom Tip: Read aloud expressively and invite students to “echo read” by repeating sentences after you with matching expressions and tones.

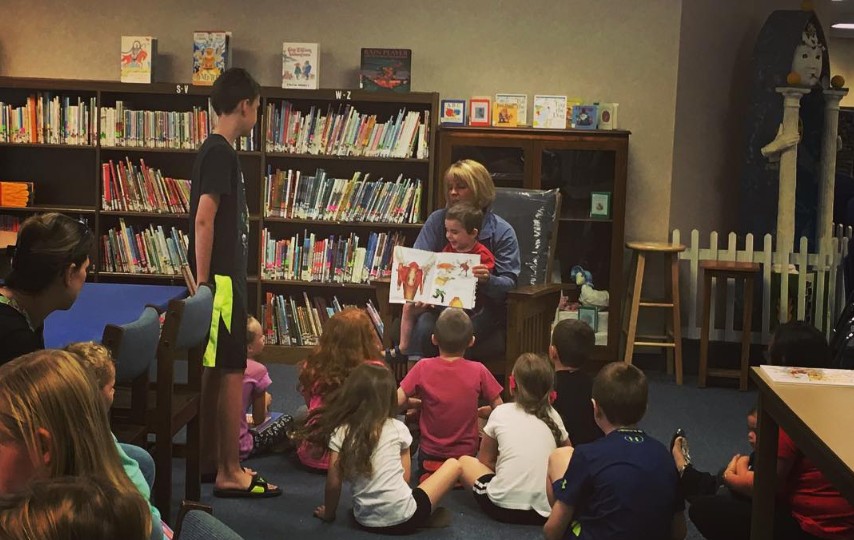

The Read-Aloud Advantage: Creating Confident Readers

Research consistently shows that children who are read to are more likely to become strong, independent readers. A landmark study by the National Institute for Literacy found that frequent read-aloud experiences were directly correlated with improved reading achievement (Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). Listening to stories not only builds technical literacy skills but also fosters a love for reading that motivates continued practice.

Key Insight: Children who are exposed to rich read-aloud experiences develop a deeper connection to books and become more confident readers.

Classroom Tip: Encourage families to read aloud at home by providing book recommendations and tips for making read-aloud time engaging and interactive.

Final Thoughts

Daily read-aloud time in the classroom is more than a routine—it’s an essential practice that nurtures literacy growth and fosters a love for reading. By making it a priority, educators provide students with the tools to unlock their full academic potential and instill skills that last a lifetime.

Reading aloud to children unlocks linguistic, cognitive, and emotional benefits that go beyond what everyday conversation or silent reading can achieve. By listening to written language, students gain access to structures, vocabulary, and storytelling techniques that prepare their brains for advanced literacy skills. Whether in the classroom or at home, reading aloud is an investment in a child’s academic success and a lifelong love of learning.

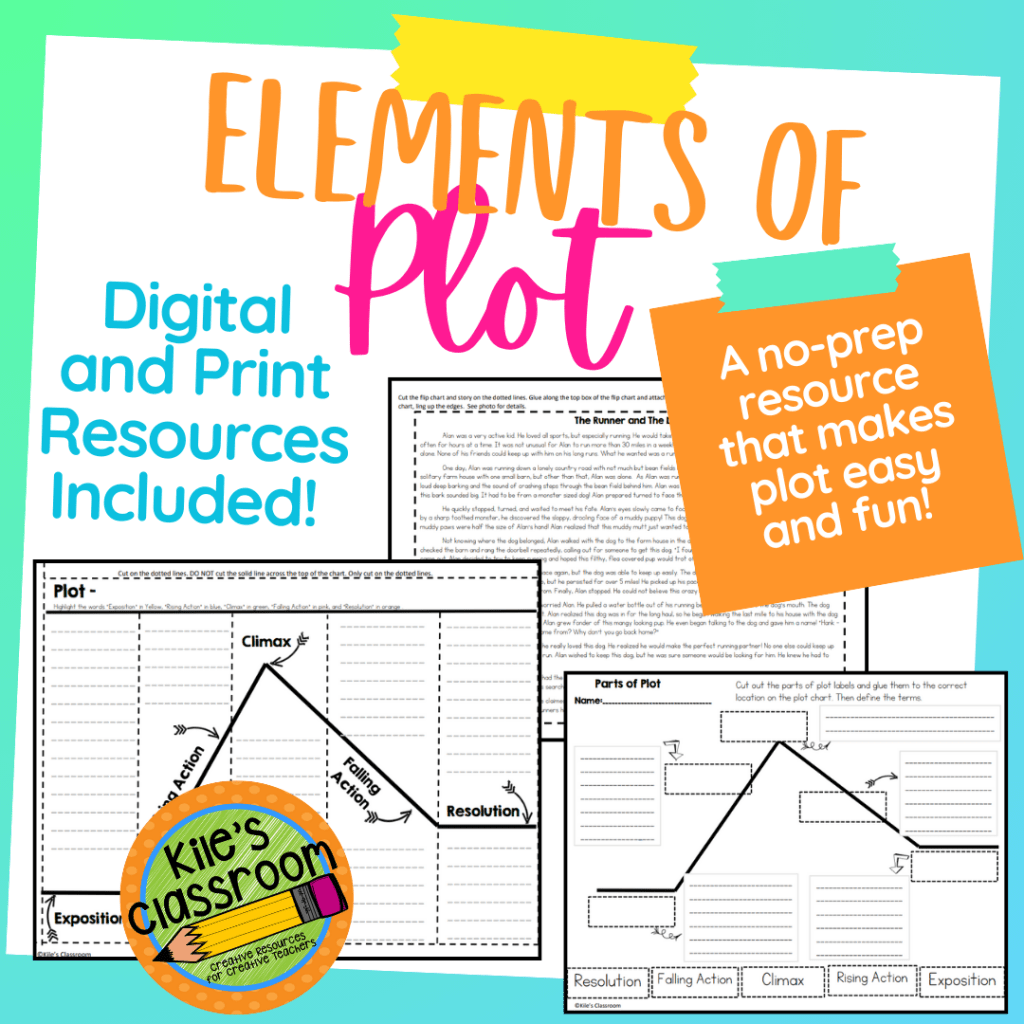

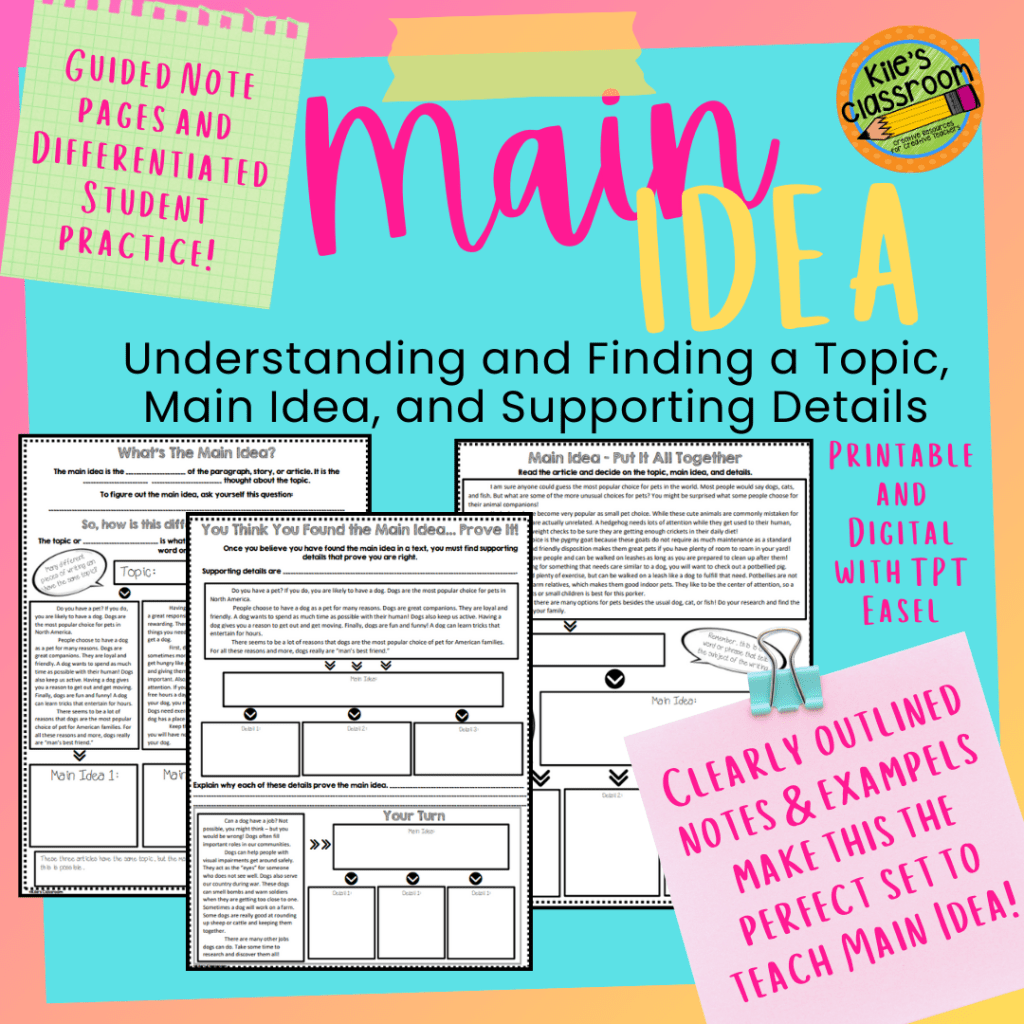

Need some support with activities that pair with any novel? Check out the resources from Kile’s Classroom by clicking the images below!

References:

- Hayes, D. P., & Ahrens, M. G. (1988). Vocabulary simplification for children: A special case of “motherese.” Journal of Child Language, 15(2), 395-410.

- Hutton, J. S., Horowitz-Kraus, T., Mendelsohn, A. L., DeWitt, T., & Holland, S. K. (2015). Home reading environment and brain activation in preschool children listening to stories. Pediatrics, 136(3), 466-478.

- Montag, J. L., Jones, M. N., & Smith, L. B. (2015). The words children hear: Picture books and the statistics for language learning. Psychological Science, 26(9), 1489-1496.

- Rasinski, T. (2014). Fluency matters. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 7(1), 3-12.

- Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. National Academy Press.

This blog was edited with AI, and citations for research were added with AI assistance. Images are of real classroom situations and owned by Kile’s Classroom. The photographs are not for public use outside of this blog and other platforms used by Kile’s Classroom.